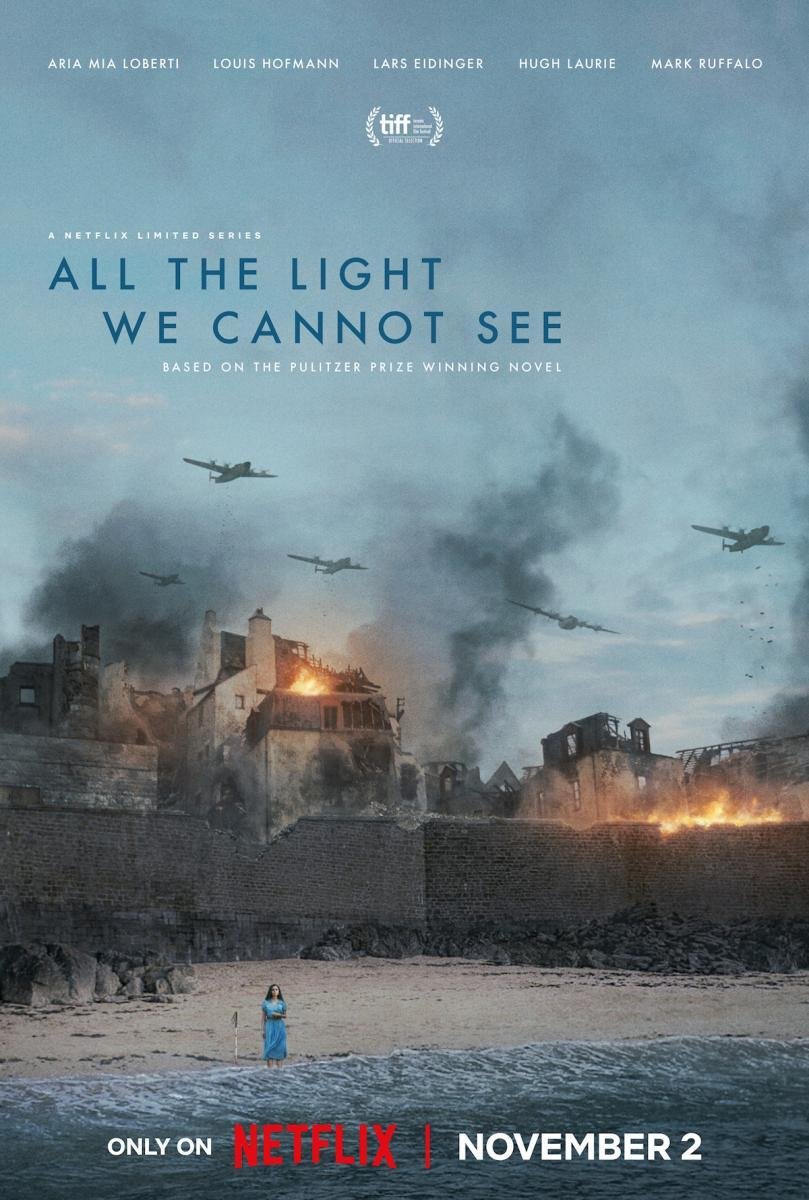

On Thursday, November 2, Netflix came out with a television adaptation of Anthony Deorr’s novel “All the Light We Cannot See.” This show appeared in just four episodes that mimic the odd chronology of the novel.

Via IMDB.

Jumping through different years in the stories of Marie-Laure LaBlanc and Werner Pfennig, the French and German characters face the violence and recklessness as the Nazis invade Paris and Saint Malo during the second World War. During a first watch, this series elicited a rather emotional response as I think of Israel and Palestine.

Both Werner and Marie-Laure are facing personal grief, yet they are forced into further despair as Werner discovers broadcasters, who are killed once he locates them, and Marie-Laure, a blind girl, is broadcasting her readings of “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” every day to preserve hope of her father still being alive. This is about getting a glimpse of light during the darkness of war, light that permeates the sounds of bombings and ruin of Saint Malo.

I found such sweetness among these young characters so full of ambition as they dream instead of dwell upon the destruction of their very homes and lives. We so often think we face real hardship at home in our beds when anxiety creeps up, and in a very real way, this is one way of suffering. But this series and Doerr’s story convicts me of some beliefs I hold simply because it is comfortable and convenient to do so. Would I hold the same sentiments as I do now if I were thrust into a situation like these characters?

“All the Light We Cannot See,” the novel, is full of such colorful descriptions, like the yoke of an egg tasting and feeling like warm sunlight to this blind girl. In contrast, the Netflix series is so much more conceptual, narrative and probably hitting home for many right now. War is a constant threat in this story, as it seems to be now, and yet the addition of a blind character like Marie-Laure gives the story such a different tone. She cannot experience war through sight. Her devastation is different, because hers is a devastation of absence of her father, not the presence of war. Werner’s devastation is in living with himself as he finds broadcasters and they are killed because of him.

Watching the series was almost difficult. There are so many films that reference all the vast destruction of World War II, while not at all helping us correctly view the situation, especially as Christians. How do we view devastation holistically? What sweetness can be retained during war?

We are simply human. Werner and Marie-Laure are not at all thriving but simply living. Werner and Marie-Laure share a memory of a professor who used to broadcast to children about only lovely things. They both cling to this memory to survive. They live for the light the professor describes, even though they cannot yet see it. This is a direct correlation to our walk as faithful servants of God. We are to become like children because children are good at preserving hope and enjoying what is meant to be enjoyed. War is not the end.