If you read the news much, or have friends who think they understand politics, you most likely have felt the hopelessness that this fallen world seems to cultivate effortlessly. Greta Thunberg sees our world as in a crisis that worsens with each sunrise: “Today, we use about 100 million barrels of oil every single day.”

But not all the news is terrible. One global trend of the 21st century (and 20th century) is the growth of Christianity in the Global South (the term used for Africa, Latin and South America, and Southeast Asia). Christians here in the West aren’t quite sure what to do. Church attendance in North America falls, but African and Chinese churches increase daily.

Theologians too, try to figure out what to do with this massive demographic reversal. What will the world look like when the seminaries are in Princeton and Dallas but the Christians hail from Nairobi and Mumbai? While Western theologians (whether conservative, liberal, Calvinist, Arminian, etc.) try to claim African churches under their respective banners, they ignore what these African churches actually care about.

Most African Christians are not interested so much in what exactly it means that Scripture is infallible. They don’t find a need for heated debates about predestination and free will. Their first theological priorities don’t have to do with credo vs. paedobaptism or losing one’s salvation or the existence of hell. In places where hunger and persecution are rampant, theologies of suffering and healing take precedence over theologies of predestination and Scriptural infallibility.

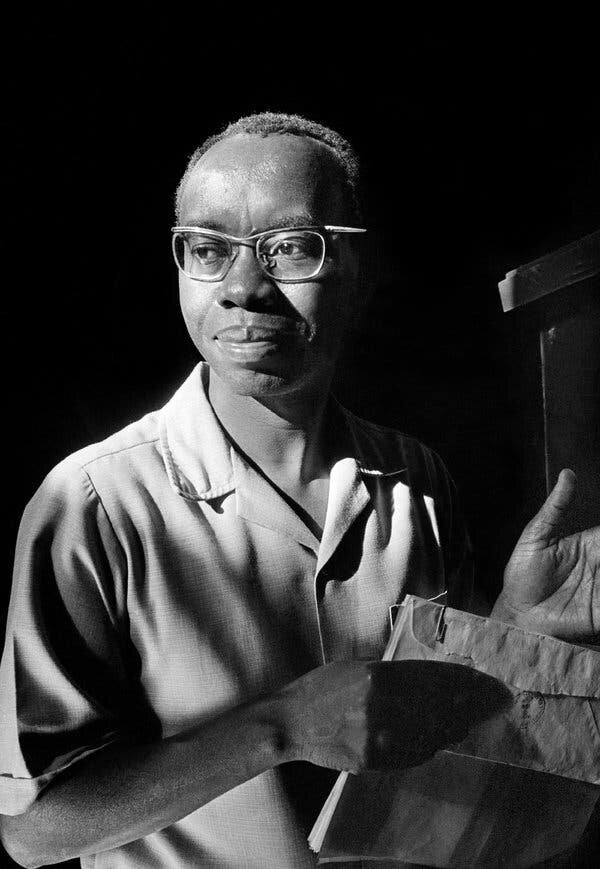

Recently deceased Kenyan theologian John Mbiti argued that “if theology has any contribution to make to the church … then it should be a healing contribution which accompanies the church wherever it is in its disfigurement and its martyrdom.” How much use is a theology for the poor coming from those who “can sit down in our library carrels and theologize comfortably?”

He points out that as Christianity grows in the Global South, the Western hubs of theology will become more and more useless as they address questions that will be largely irrelevant to the Christian farmer in central Africa, the sick child in an urban slum, or the illiterate local village preacher. After all, what good is an understanding of the Zwinglian or Lutheran view of communion when you can’t even count on reliable daily bread on your own table?

I am not saying that the debates of Western theology are meaningless or unnecessary. Rather, we should recognize them for what they are: struggles unique to our context and not of utmost importance to all Christians of all places and times.

Mbiti does not like the way that we in the West elevate our theological issues to be of primary importance in the theological world. His concern is that our seminaries and schools teach a theology that (particularly for those going out to Majority World contexts) produces theologians “bearing a watered-down theology.” He sees the current theological system as the theology of the rich and highly educated, when it ought to also be informed by poor, uneducated, or generally overlooked communities.

Ultimately, Mbiti’s call is for us Westerners to be slow to speak and swift to listen. He says African churches have learned to theologize with us about our concerns and “would like you to theologize with us, and also about our concerns.”

This may not seem to mean very much to us here at Covenant. We don’t often come into contact with the theological concerns prevalent in Africa. We don’t see much of a need for theologies of suffering, ancestors, witchcraft, famine, demon-possession, or political liberation. But we should recognize these as important considerations to many brothers and sisters all across the world, and we must not laugh or consider these to be inferior concerns.

The West has all too often looked down at the Global South as playing catch up to us. This arrogance has unfortunately found its way into the theological sphere as well. Recognizing that our theological issues are contextual should help us to grow in humility and willingness to listen to concerns of Christians around the world. As globalization continues, shutting our mouths and listening will become more and more essential.