I think I came to college half asleep. I was unaware of the world and largely unaware of myself. Like many, I entered the mountain with hesitant readiness but was quickly met with rich conversations and ideas about life that seemed to pull me out of my subterranean stupor. It was here in college that I became awakened to my own body. Sure, I’ve always had one—anyone reading this probably has one as well. But I only understood my body insofar as that I did not enjoy its appearance or understand its worth. The quiet conversations of college fostered an awakening of my body, and I began to see the insidious brokenness that had crept into my pores throughout the years.

Granted, this is no new or sexy topic. The body has been debated, used indifferently, and even misunderstood since that first, poignant sin (I’m sure you know the one I am talking about). But I think that there may be a tendency within the Christian community to baptize the great problems of the world with “The Fall,” and the solutions to the intricacies of life with “God.” It is between these lines that we see the problem of our physicality as much greater, and God’s grace far fuller. The problems our bodies and souls grapple with daily deserve to be met with something larger than ourselves, and answers that can only be met with faith in Christ and faith in the body of Christ.

The familiar words of scripture that tell us we are created in the imago dei are familiar and lend themselves to the mystery and beauty of our earthliness. But bodily discomfort, dissatisfaction, and even despair are very real things. You can’t live on a college hall with twenty women and not hear, see, and feel the scars of brokenness that manifest themselves in our physicality. I can only assume the same is true for men, similarly surrounded by other men as potential objects of comparison and confusion.

Which brings me to the heart of this conversation: the body of Christ. We can ask ourselves if we are doing embodiment well, but without the bodies of others as support for our falterings, we remain a part of the ongoing problem. It is with mysterious faith that we come to understand our place as physical beings on a physical earth, continuously redeemed by a physical Creator.

The Incarnation of Christ is no small or romantic notion; Jesus took on flesh because of our messy flesh. Jesus died because of our desperate and deeply rooted woes, even the ones that often go unnoticed or uninformed as problematic toward our theology and doctrine. Christ’s coming to earth only pulls us closer to the physicality that is our brethren and our world—the humans around us.

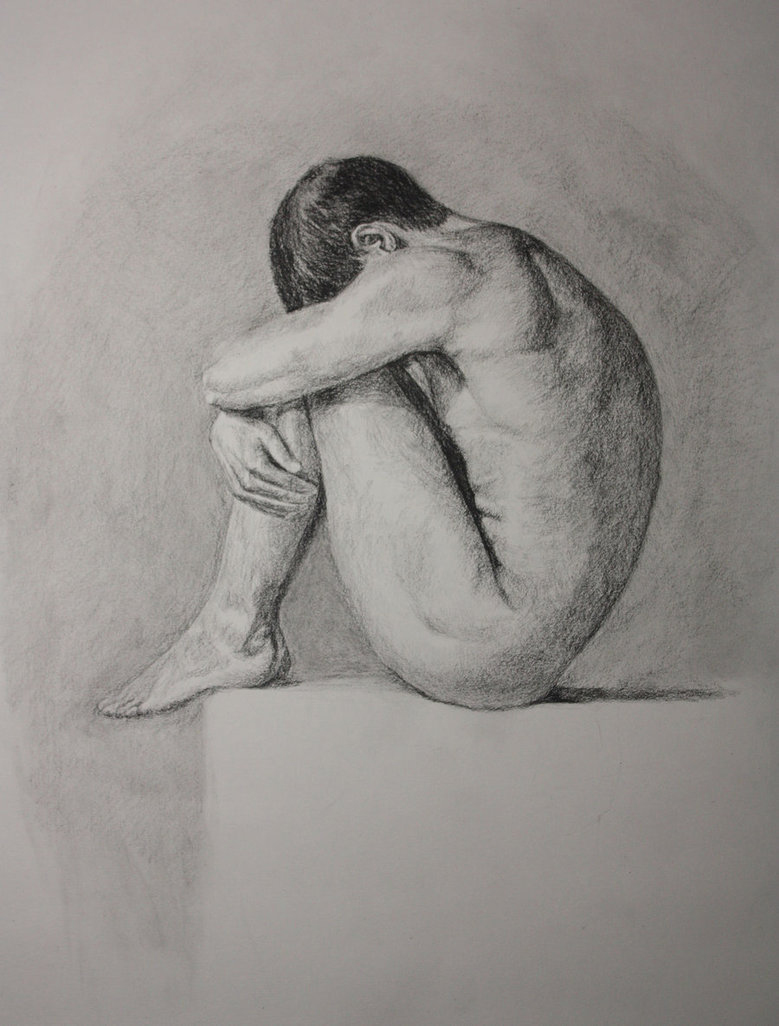

I believe this quiet stirring in my physical being is indicative of a deeper problem: a need for fulfillment. There has not been a distinct voice in the church that has sought out the verbal goodness of present physicality, especially amongst the pressures of culture and comparison. Impaired by our identities and understandings, we tend to latch on to the salvation of our souls, ignoring the gap between our physical bodies now and our perfect future bodies. But this space in-between is wide and it is real, and there is ample room for isolation and false independence to become our savior. And so I must make an appeal: for the man experiencing low self-esteem for reasons unnoticed, for the woman unable to articulate her bodily anxieties, resting in shame.

In understanding our own bodies better, we can better love and understand humanity. Sounds simple, right? I have found that this it is no easy task, but that practicing honesty within community only acknowledges our need for something greater than ourselves; this is often met in the presence of others, and healed in the embrace of Christ. In earnestly wrestling through the tensions we experience while on earth, bodily and within, we are living out the longing for what is to come: worshipping the triumphant grace that is our Incarnate Savior. The body is good.